Have you ever tried researching your family history? Maybe you’ve been doing it for decades. Perhaps, like me, you made a start several years ago, but life got in the way. Or you might never really have thought about it until recently, if ever.

After my grandmother passed away about ten years ago, my mother and I began researching her side of the family tree. Then, I became involved in writing Many Hearts, One Voice and kind of abandoned her. However, I discovered that many of the resources we’d utilised in searching out ancestors were equally useful when looking for the women who’d founded the War Widows’ Guild.

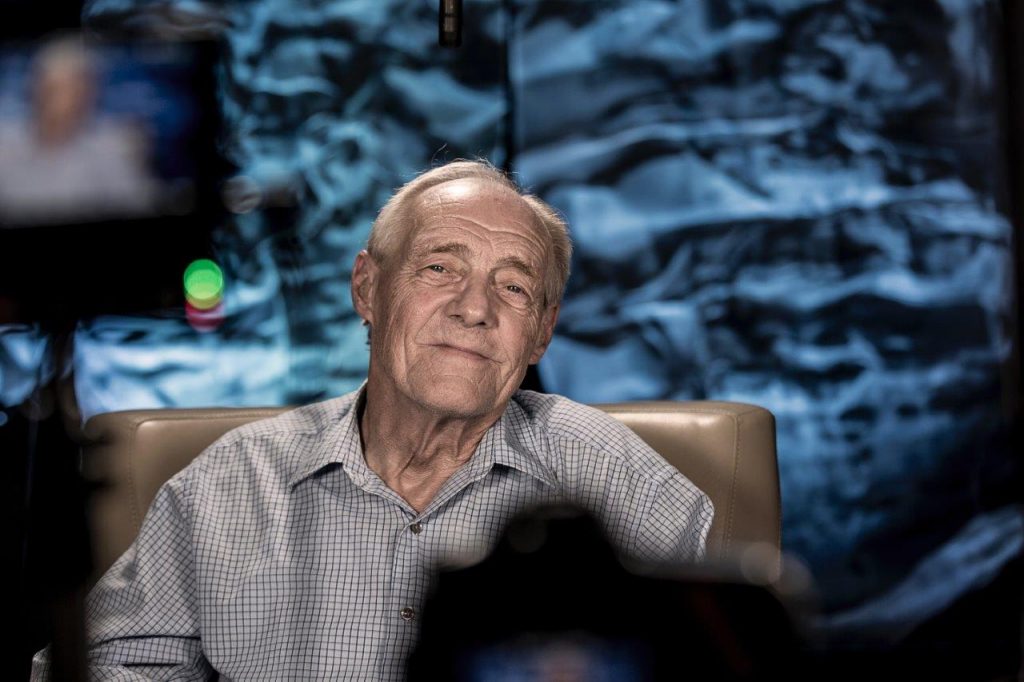

This year, I have felt a sense of urgency about my father’s ancestors, especially his mother and her family. She too passed away about a decade ago, but my grandfather is still alive. At 94, he still lives independently, with a sharp mind and a willingness to be my co-collaborator.

So, I’ve got back to study. I didn’t mean to. Honestly. But when a friend suggested checking out the family history units offered online through the University of Tasmania, I decided the external deadlines could very well be the motivation I needed to stop talking about it, and actually write my grandmother’s story.

Here’s some of what I’ve been learning.

1. Relish being the Family Detective

When researching your family history, you can go around in circles. You can discover red herrings. Sometimes there are ‘facts’ that actually aren’t, such as family stories or supposed links on someone else’s family tree. But when you confirm that a new discovery is correct, or an address on a death certificate leads to a whole other branch of the family, it is unbelievably exciting. I say unbelievable because an onlooker may not understand your enthusiasm, instead looking at you as if you’re not quite right in the head.

If you’ve been there, you’ll know what I’m talking about, and I encourage you to continue relishing each new sliver of information. Don’t give up; it will be worth it in the end.

2. Check Your Sources

Don’t accept some stranger’s family tree on Ancestry simply because one of your ancestors appears on it. You can invent an entire new bunch of ancestors that way. Unless it has external collaborating evidence, such as a birth certificate or will probate, I employ a healthy degree of scepticism and place it in the ‘possible’ category until I’ve tracked down the relevant documentation myself.

Similarly, family stories that have been passed down the generations can turn out to be partially incorrect, or completely untrue. For example, there was a suggestion that my mother’s grandmother was related to the pirate, Captain Kidd. In fact, a quick google search offers several reasons why this is highly unlikely, but would not have been so easily verified or disproved several generations ago.

3. Reference as you Research

Whether it’s family history, a uni assignment or a full-length book, it’s important to be identify where your information has originated from, whether that’s so you can find it again, or for future researchers to build on your hard work. There’s nothing more frustrating noting that your great-great-grandfather died in 1936, but having no idea why you believe that to be true. It’s much easier to reference your sources as you find them, rather than having to comb through every resource before finding the info again.

4. Ask those Questions

After my mother’s father died, my grandmother packed up her home of half a century to move closer to my uncle. I helped her sort through my grandfather’s study, which included a large collection of photographs. Although it was the perfect opportunity to find out more, I didn’t ask many questions. This was partly because she always seemed reluctant to talk about her past, but also because my toddler son gave me little time or patience for trawling through a bunch of old photos and ephemera.

The one saving grace is that I knew enough to salvage the photos she thought unworthy of keeping. But if I had my time over, I’d dare to ask more questions. I’d be more interested while I still had the chance.

5. Record Your Living Relatives

I spent most of last weekend, listening to a cassette (yes, an actual tape) of my uncle interviewing my grandmother and her brother. Recorded in 1985 (yes, you read that right), they spoke about their childhood, parents and grandparents. I heard some wonderful anecdotes about growing up in Ireland in the years between partition and the Second World War, which would have been lost if not for this recording. How precious to not only have the information they offered, but simply to sit and hear their voices.

So, if you have elderly relatives whose minds are intact, I encourage you to make contact and book a time to record an oral history interview with them. Ask them those questions, and listen to their stories, before that family history is lost forever.

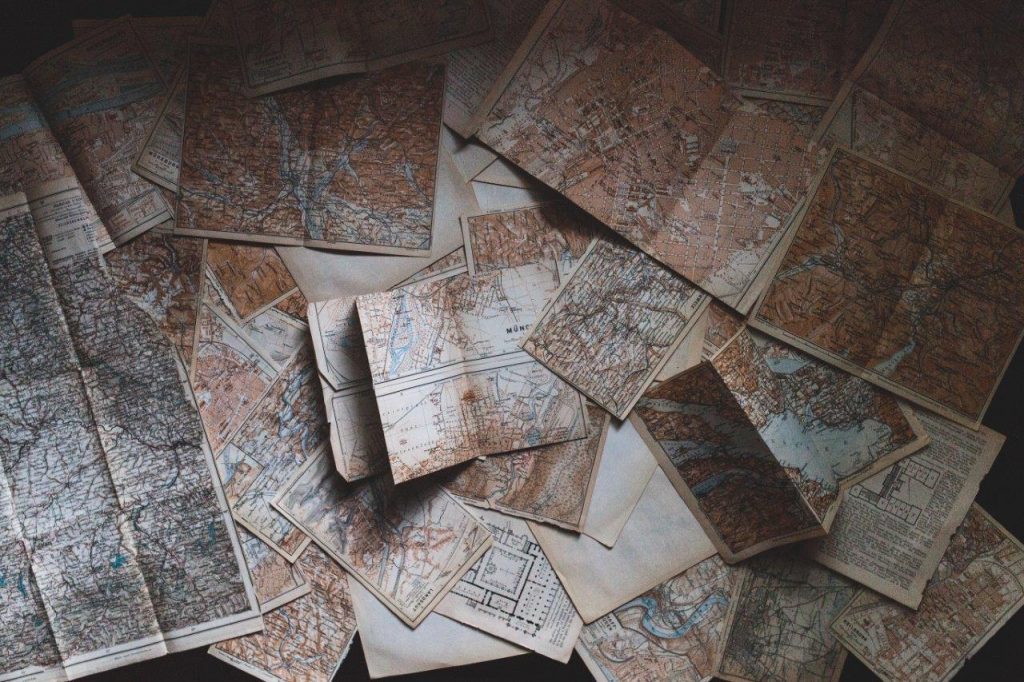

6. Use Maps

Maps are a wonderful way to help visualise where your ancestors lived. Currently, I’m exploring what Belfast might have been like in the early 1900s, and trying to gauge how closely my grandmother’s extended family lived to each other. It raises other questions, too, such as what transport did they use? How often did they visit each other? What shops, churches and other buildings were part of their weekly routine? Where was the skate rink my grandmother mentions in the recorded oral history interview?

UTAS touch on the usefulness of maps in their Introduction to Family History unit, and expand on it in Object, Place, Image, which includes creating an annotated map of a place your ancestors lived. I managed to locate a 1947 map of Portsmouth and Gosport through the National Library of Scotland, with which I traced the routes my grandparents would have walked and bussed during their time there.

7. Explore Contextual History

There will often be times when the details you’re seeking are frustratingly scant. Exploring the contextual history of a particular time period can indirectly fill some gaps.

Exploring what else was happening in your ancestor’s world, whether that be locally or internationally, can offer insights into his or her life, and create interest for your reader. For example, my great-grandmother lived in Northern Ireland between the turn of the 20th century and the Second World War. By researching what else was happening at that time led me to realise that she most likely witnessed the launch of the Titanic and that when news of its sinking emerged, she would have been a teenager dealing with the death of her own father.

What important, or simply intriguing events did your ancestor live through? How could you weave this through his or her life story?

8. Writing Your Family’s Story is not a Linear Process

While researching and writing Many Hearts, One Voice, I regularly moved between researching and writing. If I had waited until my research was complete, I would still be working on my first draft. Instead, I’d draft a section using the information I did have. As I did so, I added in questions I still wanted to answer, gaps I wanted to fill.

A family history is no different. My experience suggests that it doesn’t matter how long you’ve been researching your ancestry, there will always be gaps, always be something more you’d like to know. If you wait until you have all the facts, you will never start writing your family history in a form to share with others.

9. Tell a Story

We are hardwired to tell and hear stories. One of the reasons I took so long to write Many Hearts, One Voice was that I didn’t want it to be a list of dates and events. I wanted to tell a story. I wanted to shape the information I’d uncovered into a narrative that showed what life was like for these women who had waited for and lost their husbands, before gathering together and standing up for the rights and welfare of others like them.

I believe family history can work the same way. We can write it in a form others want to read, even if those readers are simply our extended family. There are numerous writing strategies that can help you do that, and these will be the focus of a future post.

10. My great-grandfather was a scoundrel

Okay, this is more a confession rather than a tip, but I’m sure we all have one. Actually, more than one of my great-grandfathers is a scoundrel, but this one’s on my father’s side. He was apparently considered a ‘lad’ before he discovered God and became a changed man. Whether that was before or after he married my great-grandmother, I am not yet sure. He was married at least once previously, possibly to a minor, with a wedding two months before their daughter was born. Not such a big deal these days, but it would have been back in the late 1800s. Some of this is still in the ‘tentative’ category, but it certainly makes for interesting, and at times frustrating, research.

Once upon a time, families covered up family scandals and secrets, but as a writer (and reader), it makes for much more exciting reading. Of course, there are a few ethical issues to consider when revealing such stories. As the family historian, you will need to make some decisions about how much to reveal to a wider audience, balancing a story’s interest and intrigue with the feelings of family members who are still living.

Over to You

What have you learned about researching and writing your family history?

What other resources or information would be helpful for you at this point in your process?

Great tips Melinda

Thanks, Sharon! Hope some of them are useful to people.