I’ve just returned from a short trip to Bintan Island in Indonesia – part holiday and part support crew for my husband, who was competing in a three-day bike race, the Tour of Bintan. With the race as the major focus of our stay, I saw only a tiny part of what there is to see on the island, mostly within the confines of our resort, but I loved what I saw of it and its people, and want to explore more of Indonesia.

Most mornings, I woke early to connect in with my #5amwriters club, then walk along the beach.

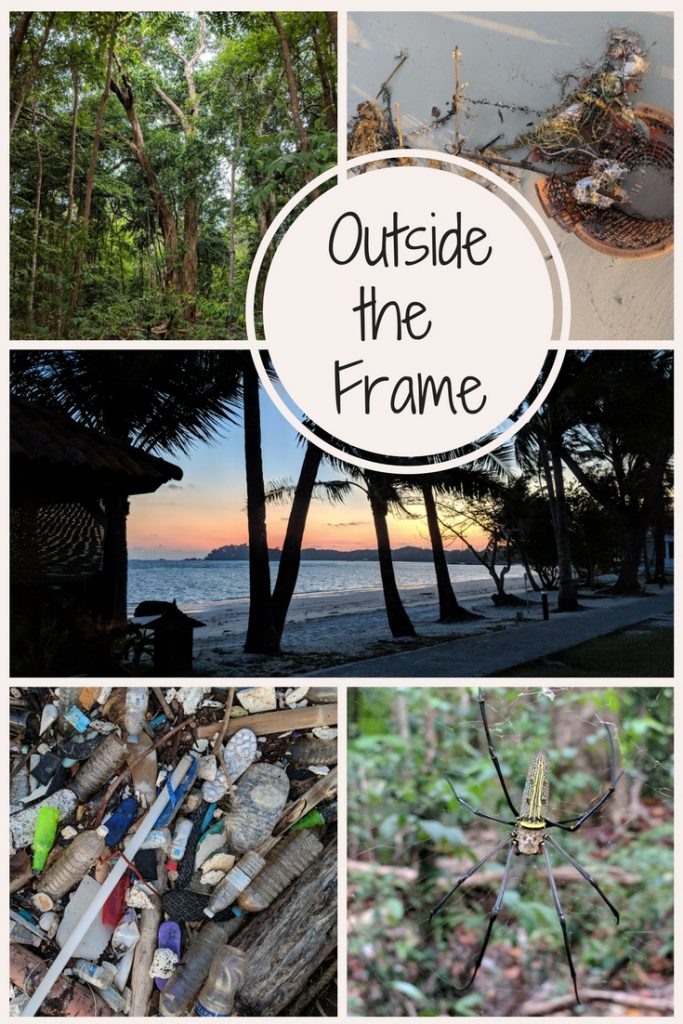

I’d eventually reach a sign instructing me not to go any further, as I was leaving the resort grounds and the beach would not be ‘patrolled’. I ignored the signs and kept walking. Rather than any personal threat, this is what I found:

Now this isn’t the remains of some party by either locals or tourists. This is the debris that blows in on the currents from elsewhere, and is then discarded by the tide. If I’d stayed within the boundaries of the resort, I would have avoided this sight, because each day local workers sweep the beach, gathering up the rubbish washed ashore overnight. Sometimes, this included pools of oil, a side effect of an island nudging a major shipping route in the South China Sea.

It got me thinking about photography – and life – about what we choose to include in an image, and what lies just outside the frame. This was partly prompted by a recent article about the way some young people navigate between multiple accounts on one social media platform. One account is the curated image of themselves, which they show the world, while another is a private account they share with only their close friends. The article says:

‘Private, less visible, accounts allow the opportunity to move away from the carefully cultivated, public persona on their real Instagram account – and present a rawer, “This-is-the-real-me” personality to a smaller group of closer friends.’

At one level, I’m sad that our young people are already feeling the pressure of perfection, that the ‘real me’ is not okay. At another, perhaps there is some wisdom in knowing what’s safe to share with the world, and what you should only tell good friends. After all, there is a fine line between safety and open vulnerability.

I tend to err on the side of keeping things to myself, though, and I’m pretty sure I know why.

At age 12, my family moved to a remote mining town in northern Australia. Having spent the previous year travelling the country, I was excited to be staying in one place (a house was a bonus), meeting new friends (which came easily while travelling) and starting high school. The first day at my new school began with promise. The first girl I met invited me to sit with her group at recess. By lunch time, however, I’d failed the acceptance test. Having parents who were also new teachers in town were apparently grounds for rejection: exclusion, name calling, put downs, and fingers slammed in a classroom door.

One thing was clear: Being me wasn’t good enough.

I did eventually form other friendships, but instead of being wonderfully, unapologetically me, my insecurity and flimsy self-worth meant I spent my energy trying to determine who and what others wanted me to be. Afraid to voice my views, I carefully gauged the opinions of others, and edited mine accordingly. When, at 18, my then boyfriend asked me a series of questions, I responded, ‘I don’t know’ to every single one.

Somewhere along the line, I forgot how to be myself.

Brene Brown says that ‘True belonging is … not fitting in or pretending or selling out because it’s safer. It’s a practice that requires us to be vulnerable, get uncomfortable, and learn how to be present with people without sacrificing who we are.’ (Braving the Wilderness, p. 37).

How do I – we – live in such a way that we don’t feel the need to fit in or pretend or sell out? How can the person I show the world be congruent with the person I am in private? In the words of Parker Palmer, how do I ‘live divided no more’? How do I show up as myself in a world that increasingly wants to tear others down?

What I do know is this: the answer doesn’t lie in seeking perfection. Life has a complexity, both beautiful and messy, that is often missed in the carefully curated images we share on social media.

When I worked as an English teacher, one of the tasks I undertook with my students was to analyse the news. One year this happened to be around the time of the Melbourne Cup, the race that apparently stops a nation. We viewed two different news stories, and it was as if we were viewing footage of two different events. One news item showed people wearing elegant dresses and tailored suits, sipping champagne. The other revealed dishevelled young people who’d drunk too much and were behaving badly. Each team of reporter and cameraman had selected different details to include ‘in the frame’.

The reality was that both these images were part of the same event, just as the beautiful sunrise and the discarded rubbish were part of my experience of Bintan Island. A picture may tell a thousand words, and yet no picture can tell the whole story. No wonder photos are called snapshots – a micro-story rather than a novel with complex subplots.

There is nothing wrong with the art of a beautifully captured shot, for it can point us to wonder and joy in the world. But I also recognise the messy, imperfect and quirky scenes that lie outside the frame. All are part of me and the world in which I live.

Brene Brown has this advice:

‘True belonging and self-worth are not goods; we don’t negotiate their value with the world. The truth about who we are lives in our hearts. Our call to courage is to protect our wild heart against constant evaluation, especially our own. No one belongs here more than you.’ (Braving the Wilderness, p. 158)

For me, part of learning to ‘live divided no more’ is to reflect on the question: Who was I before the world started telling me who (and how) I should be?

I’m still discovering the answer, but in doing so, perhaps I – we – will realise this truth:

‘True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are.’ (Braving the Wilderness, p. 157)

And that includes embracing both what’s inside and outside the frame.

Oh, gosh. You just made my brain hurt with what it now has to think about. What a concept – outside the frame. Yes, funny how there is a mirror in life to ‘sweeping things under the carpet’ – or in the case of Bintan resort – out of the frame. As if guests not seeing, and therefore not knowing it’s there makes it all okay somehow and the polution is not an issue – everything is still holiday picture-postcard perfect.

Excellent post, Melinda. Thank you for writing it, even if you made my brain hurt.

Hi Lily, thanks for reading and apologies for making your brain hurt!

An exquisite post, Melinda. So many truths. Thank you for sharing your thoughts. 🙂

Thanks so much, Louise. So glad you liked it – thanks for challenging me to write more of me into my posts. 🙂

Thanks for your honesty. Your words have many rings of truth at whatever stage of life we find ourself in.

Thanks for taking the time to read it, Tash, and glad it rang true for you – and lovely to hear from you, too!

Nice Melinda.

I think we should all look outside the carefully sculptured frame that is presented to us by the world and view the whole picture. Watching my grandchildren grow up I see, and fear, that that they are already adapting to the world far before they will ever have any sense of self. My hope and commitment is for them to realise that who they are now is just their automatic response to the world and their future need not be so. Life is a just story, and through choice and commitment they can create their own story, a future free of the invisible constraints of their past.

Hi Ken, your grandchildren are indeed blessed to have someone like you in their lives to help them be who they truly and innately are. So important for our young people to have those inter-generational connections, too. Here’s to them creating their own story. xx

Melinda, I really loved this piece – I read it back when you published it and it’s been saved in a browser tab ever since to remind me to comment (oof, took me 6 weeks). Thanks for sharing this post – I love the undercurrent of wholeness and identity (and authenticity) that runs through it.

Thanks, Holden. That means a lot that you enjoyed it. By the way, you sound like you keep tabs open for weeks on end like me, waiting for me to get back to things I want to read. I just counted 30 tabs open (and I just closed half a dozen).