“The only thing left my friends, is to forget. And you forget, not by reopening a court case, by throwing someone in jail. No, F O R G E T [he spelt out the letters]. That is the word, and to achieve that, both sides have to forget.”

Augusto Pinochet 13 September 1995

Today marks 45 years since September 11. If you’ve done your maths, you might be scratching your head since the attack on the Twin Towers was 17 years ago. But that’s because I’m talking about the other September 11.

Tuesday September 11, the one of 1973, not 2001, was an overcast spring day in Santiago, Chile. The Andes Mountain stood proud and impenetrable above the cloud and smog. The trees were bursting with fresh leaves after the barren winter. As my friend Cecilia and her sister set out on their milk round that day, they had no idea of the events that were already beginning to unfold.

By the end of the day, their president, Salvador Allende, would be dead, and Chile would be under the violent rule of Augusto Pinochet.

Cecilia was 14 when Pinochet staged his military coup. That’s the same age my daughter is now. I can’t imagine Miss A having to experience such fear, trauma and loss.

Curfews. Arbitrary arrests. Secret police. The disappearance and torture of loved ones. Always having to look over your shoulder to see who’s following you. Being super careful of what you say and to whom, never sure which neighbour might turn you in for whispering words against the regime. This is no Dystopian fiction; this was Cecilia’s reality:

“We lived in constant fear. Any sense of safety, even inside our homes, was obliterated. For two years, my father slept in his clothes. He’d hear the military outside and he’d say, ‘This is it; they’re coming for me.’ And when they passed by, we’d thank God he was still here.”

Seeking Refuge

Not long after the coup, the Whitlam government began allowing greater numbers of Chilean immigrants into Australia. In doing so, our government became one of the first to offer sanctuary to those fleeing Pinochet, a compassionate act acknowledged at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago. In 1971, there were about 3,7600 Chileans living in Australia. A decade later there were 18,740.

Cecilia survived under the dictatorship until 1987, although she knew many who did not.

One day, the terror came so very close to home, when her boyfriend was arrested. Initially, nobody knew of his whereabouts. Only some quick thinking by Cecilia and other family members led to the discovery of the police station where he was being held – and his subsequent release. However, they were warned he was in danger of becoming one of the ‘disappeared’ – those who were arrested and never seen again. With the help of a local Catholic priest, they sought protection from Australia.

Within three weeks, the couple had planned a wedding, packed a suitcase, and were boarding a plane bound for Australia.

“As my plan rose into the air and over the Andes, I watched my home grow smaller and smaller until finally it was gone altogether.”

Cecilia and her new husband arrived in Australia seeking refuge, but she is far more than simply a refugee.

She is a wife and a mother. A sister and an aunt. And, of more personal significance, she is my friend and confidante.

When I first met Cecilia 15 years ago, she embraced my children and loved them like a favourite aunt. In fact, she’s been a ‘baby whisperer’ for dozens of children – and a saving grace for numerous young mothers. She cared for me while my daughter was seriously ill. She’s demonstrated that just about anything can be fixed with a screwdriver, scissors, or needle and thread. She exposed me to Chilean artists such as musician Victor Jara, poet Pablo Neruda and author Isabel Allende. And she has shown me what it means to have almost nothing, yet still inhabit a kind and generous spirit.

The Power of Story

When I first asked Cecilia if she would be my subject for a biography unit during my Honours year, it bewildered her that anyone could be interested in her story. Thankfully, she agreed anyway, despite the fear she relived in doing so. It could be said that if I hadn’t heard Cecilia’s story and written a chapter of it for that uni assignment, I may never have come to write Many Hearts, One Voice: the story of the War Widows’ Guild in Western Australia.

In writing about Cecilia’s life, I discovered the power of story, and the value of deeply listening to others. Without Cecilia’s story, I wouldn’t have realised I wanted to tell ‘invisible’ stories, and it’s unlikely I would have considered the experience of war widows. Thus, it seems significant that the year which ended with the publication of Many Hearts, One Voice began with me accompanying Cecilia to visit her family in Chile.

In some ways, I took the trip at the wrong end of the writing process. For me, experiential research, where I immerse myself in the physical space of a place, is a vital component of preparing to tell a story. Yet, in researching Cecilia’s story, I’d had to rely on photos, film footage, and her own descriptions of her home and neighbourhood. So, when I travelled to Chile with her in January 2015, it was rather surreal to see the places I had previously only imagined.

Memory, History and Human Rights

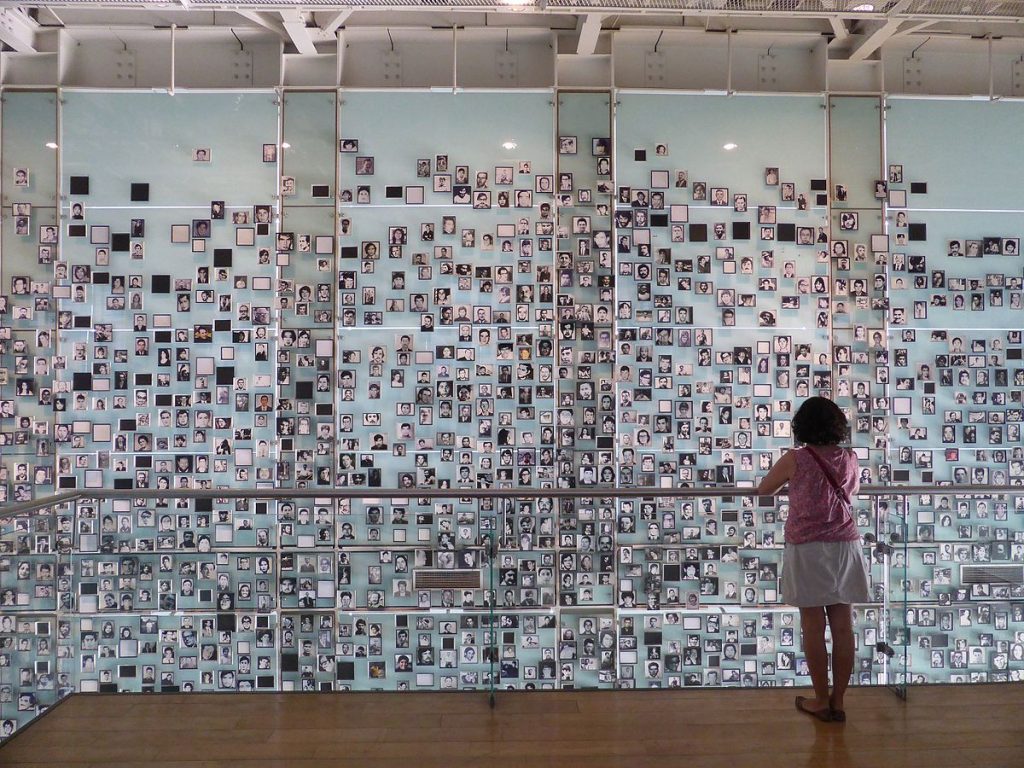

While in Santiago, we spent a day at the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos (Museum of Memory and Human Rights), which had opened in 2010. The museum aims to “draw attention to human rights violations committed by the Chilean state between 1973 and 1990”, with the hope of promoting “respect and tolerance in order that these events never happen again”.

We hadn’t been at the museum long when Cecilia pointed out a photo of a protest rally. “My mother was there that day,” she said.

Around the corner, archival news footage played on a television. Cecilia explained this was an example of the videos her then boyfriend (now husband) helped smuggle to outlying areas, hidden inside the cover of a Gandhi film. These news stories attempted to counter the propaganda played on official news channels. Being involved in such activities was extremely risky. It’s possibly the reason for his arrest, and ultimately why he and Cecilia eventually fled everything they knew and loved.

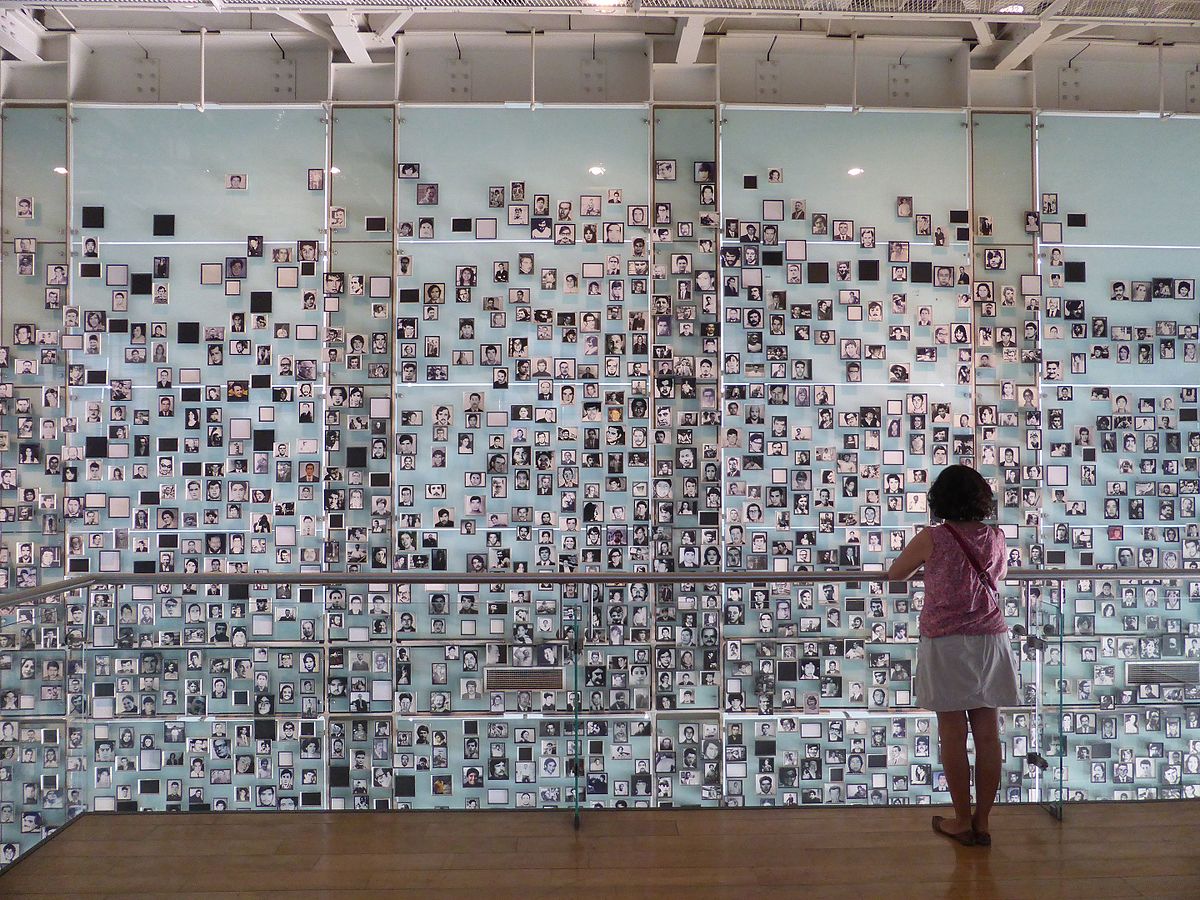

On a wall of photos – a memorial to all those who had “disappeared” under the Pinochet dictatorship – Cecilia pointed out someone else she’d known.

‘Historia’

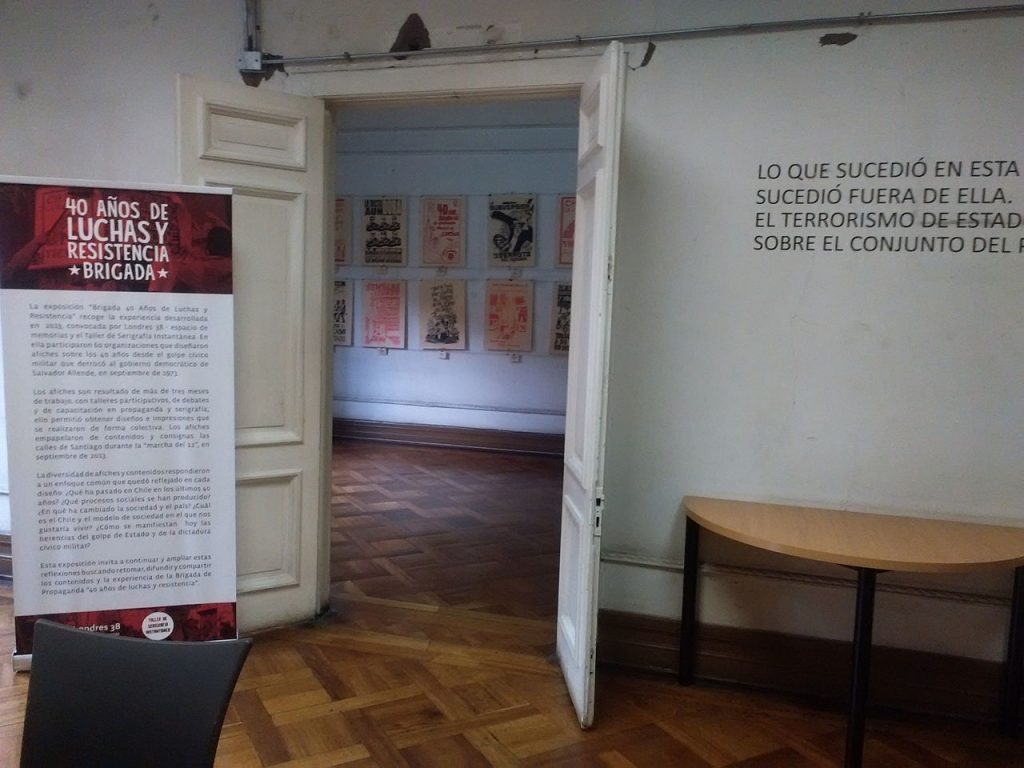

Later, we also visited Villa Grimaldi and Londres 38, both sites of torture during the Pinochet regime. Particularly moving was our visit to Londres 38, which from the street looks like any other building in the centre of Santiago.

The floodgates opened. He began telling us he’d been one of those imprisoned and tortured at Londres 38. At one point, he was overcome with tears, but continued to speak. As if he needed to share his story, to give voice to his suffering. I didn’t understand much of what he said – he spoke in Spanish and I had to rely on Cecilia to translate for me – but I could certainly comprehend his emotion.

Cecilia encouraged the man about the importance of his story; without those who were there bearing witness, then the story – the evidence – would be lost.

It’s interesting that the Spanish word for story is the same as the one for history:

historia

While Augusto Pinochet wanted both sides to forget the atrocities committed under his rule, Cecilia returns to the importance of the personal in telling about history, of remembering and acknowledging the events of the past:

“The world has forgotten what happened to us on that other Tuesday September 11. The world has forgotten because we have been too terrified to remind them. Many refuse to speak about those days, burying memories they cannot bear to remember. But I shall no longer forget, no longer be silenced by fear. I shall remember, and by remembering, my nightmares will no longer haunt me.”

I had no idea, Melinda, of this ‘other’ September 11. thank you for enlightening me with such a poignant post.

I had no idea either, until Cecilia started sharing some of her story with me. I find it especially interesting that they were both on a Tuesday, as it is this year.

What an amazing story, Melinda. Thank you for bringing it to us and a special thanks to Cecilia for being brave enough to share it.

I truly love the unique perspective you have, Melinda, in telling others’ stories that would otherwise be untold and unheard. Your beautiful writer’s voice and your heart of compassion come through so strongly in your writing. I hope you gain increased recognition for your work.

Thank you so much, Susan. That means a lot. xx

What a powerful story of one of the strongest women I know. Thank you Mindy for offering our Cecelia a voice. May your work continue.

Thanks, Lisa. And yes, Cecilia is one of the strongest women we know – more than she realises, I suspect. xx

Just as someone needs to play the notes on a page for us to hear the music, you have written and revealed the story hidden behind someone’s person’s face. Keep on, Mindy!

I love that comparison, Julie – thank you so much. xx