Are you someone who can create entire worlds in your head, like some of the best dystopian and speculative fiction writers I know? Or do you, like me, need to experience a place to be able to write about it?

Whether it’s a community history (such as Many Hearts, One Voice) or family history, or fiction, I write better when I can immerse myself in the physical world of my story. Of course, that’s not always possible, and there are times I’ve had to rely on photographs, books and film footage, as happened when I wrote about my friend’s experience of growing up in Chile under the Pinochet dictatorship in the 1970s.

Recently, though, I had the opportunity to walk in the footsteps of my ancestors – or at least the streets where they lived and worked. In this case, I was fortunate enough to share the experience with my mother, who’s researching the same branch of our family (in fact, she’s done most of the hard work).

We wanted to explore the Melbourne suburbs of Brunswick, Collingwood, Abbotsford and Clifton Hill. Being from interstate, the area was new to me, but an easy tram ride from where we were staying in the city’s centre.

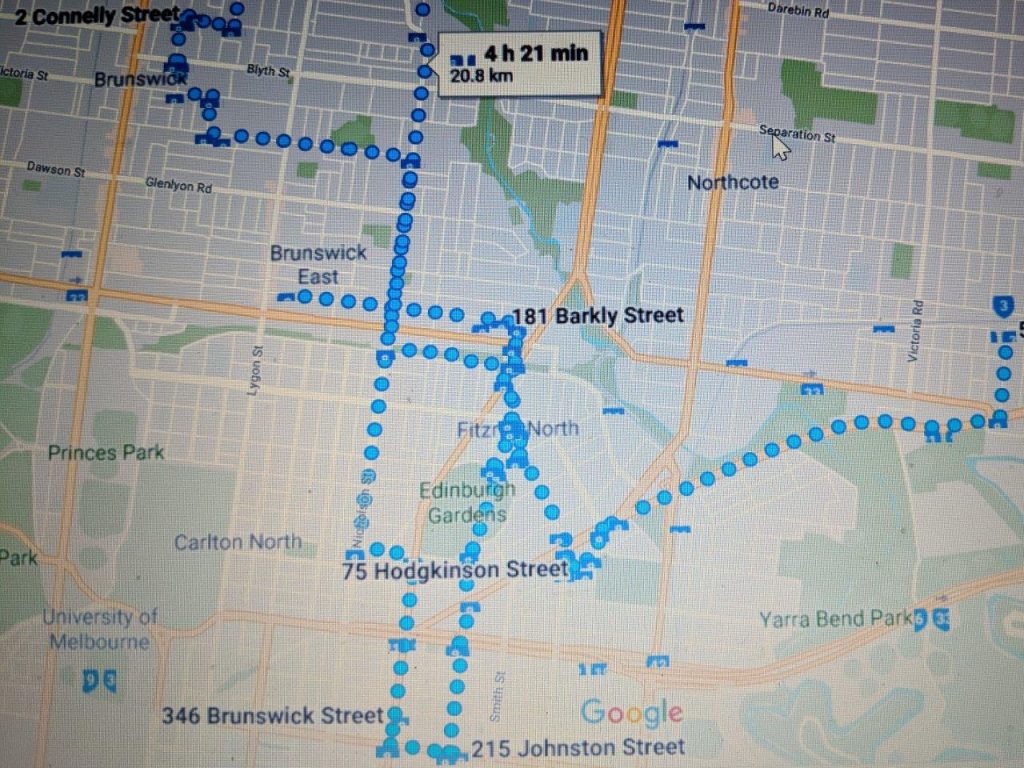

It was a cool, Autumn Saturday, and we set out armed with a list of addresses (gleaned from electoral rolls, postal directories, birth and death certificates, and war service records) plotted onto google maps.

I know nothing free is really free, and google was being paid in the data of my every move over that weekend, but I can tell you that the google maps app on my phone proved invaluable. It not only gave us directions, but the time it would take to walk, and any public transport alternatives.

The one thing google maps didn’t clarify for us was – in these Melbourne suburbs at least – you need to be very specific about the suburb you’re searching in. For example Barkly Street and Barrow Street have house numbers that start from scratch when you cross into a new suburb. So, there is a 135 Barkly Street, Brunswick, and a 135 Barkly Street, East Brunswick.

We only discovered this because we were looking for a cafe in which to eat breakfast, and an online search recommeded one at 140 Barkly Street, which in theory was right in the middle of three of our ancestors’ houses. Only, it wasn’t.

There is definitely no cafe at 140 Barkly Street, East Brunswick; however, Lucy Lockett – at 140 Barkly Street, Brunswick – has great food and a relaxed atmosphere. Similarly, the numbers in Barrow Street restarted as we crossed the border between Brunswick and Coburg, leaving us with two possibilities as to the house in which my great-grandmother was born.

We also discovered:

- sometimes a street no longer exists, or has been renamed, with further research required, probably with a map from that era.

- Wear good walking shoes if you’re choosing your feet as your primary mode of transport.

- Walking may be hard on your feet, but you’ll see more on foot than you will driving past.

- Allow more time than you think you need. We returned for a second day, after we were running out of daylight (and our legs were protesting loudly).

- If walking long distances is not your thing, Melbourne public transport in partnership with google maps is your friend.

- Sometimes that ‘just one more’ address proves to be totally worth it.

On our second day, there were still several addresses we wanted to visit. One was a fair walk away, so I first looked up a street view of the place to see if it would be worth it – and it did look ast though the street contained numerous old houses, so we set off. We did stop for a coffee break along the way, though. The extra walk was totally worth it, with the address in Clifton Hill most likely the house my great-great-grandmother Mary Negus had once lived in with her daughter and son-in-law.

More Questions than Answers

Of course, every piece of information I uncover raises more questions. Perhaps it’s because, for me at least, family history is so much more than a list of names and dates on a family tree. It’s the story behind those names. Its (re) creating the world they lived in, the local history and their social context, including things like attitudes to death and grief, which were very different to the way we perceive it today. What were their hardships, joyss and other circumstances of their lives? And then there is considering the why of where they lived, what they did and what happened to them.

Which of those houses were the same as those our ancestors actually lived in? The 1970s house in Barkly Street clearly wasn’t one of them. Another had been demolished to make way for a new road. But many of them looked as though they could have been the original buildings. I now want to research the architecture of houses across different eras. For example, when was wood, stone and brick each introduced as building materials? When was terraced housing popular? How wealthy did you have to be for a particular size of home?

In one case, ancestors Emily and Arthur Gardner had moved from Johnston Street, Abbotsford (where a modern warehouse/office block now stands), into 346 Brunswick Street, about the same time that Emily’s occupation changed from ‘home duties’ to ‘dressmaker’ on the electoral roll. Their ‘new’ address proved to be a shop, with a flat above. Was the move so she could run her own dressmaking business, or was the family simply renting the flat about someone else’s shop?

Then there’s the broader social and historical context of the time period, which ranges from the 1850s Goldrush era up to the Second World War. Nearby Sydney Road was not only the road to Sydney, but also the main route to the Goldfields. What was it like living during those gold fever days? What caused some to head off down the dusty road, while others remained in the Brunswick area as tram employees, dairymen and dressmakers?

So many questions.

I want to use these questions to find out more, to be able to use what historian Inga Clendinnen referred to as the ‘fragmented, frustrating record of “what happened”’ to piece together the story of my ancestors. But I also want to use those details as a launch pad into a work of historical fiction.

I’ll let you know where it leads me.

Over to You

What questions do the frustrating fragments of history raise for you? How might they motivate you to digger deeper and find out more?

If you’re writing fiction, how can these fragments help you recreate the time period in which your story is set?

If you could visit any place to conduct some experiential research, where would you travel to?