Tips for Young Writers: How to Write about Historical Events and People

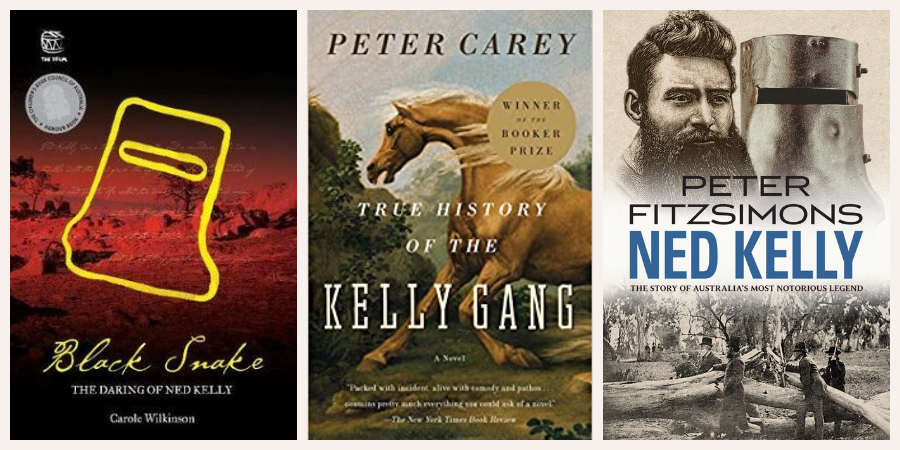

I was recently chatting to a teacher from Mt Isa in Queensland, whose class is studying Black Snake: The daring of Ned Kelly by Carole Wilkinson. One of the students’ tasks is to write a recount of an event in the book from the perspective of an individual character.

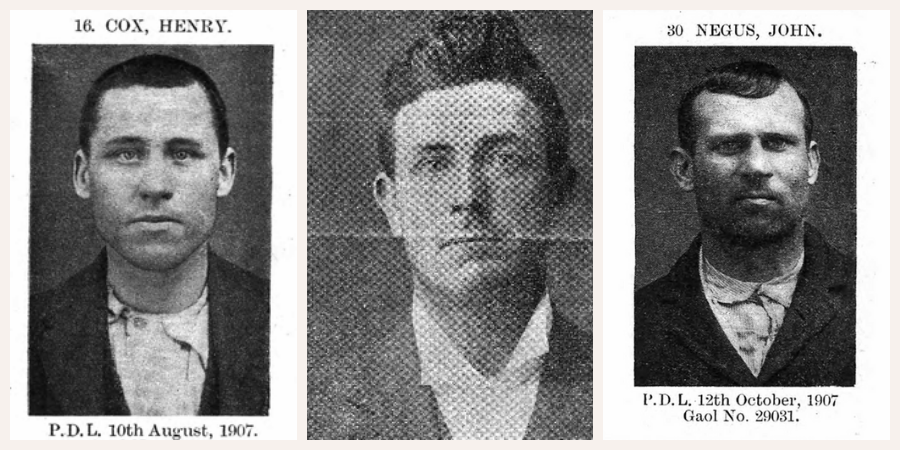

Hearing about the class researching Ned Kelly through Carole Wilkinson’s book has made me think about one of my own ancestors, my great-great uncle John Negus. Family myth suggests that my great John knew Ned Kelly; however, the connection is a tenuous one. John was born in 1873, meaning he would only have been seven when Ned Kelly died in 1880. Perhaps John was “inspired” by Ned (he was caught for robbery under arms and sentenced to ten years in prison in 1899), but it is highly unlikely there was any direct contact between the two.

Whether it’s a set task, an ancestor whose life you wish to recreate, or simply a fascination with an historical character or moment in time, there are a number of questions that can help you (and me!) make decisions about how to research and write about a chosen subject.

Choosing a Perspective

Who is usually the focus of this story or event?

Who else is part of the story, but whose perspective is often not heard? In other words, whose story is sidelined or silenced in the telling of these events?

Other than the usual focus (e..g Ned Kelly), whose story fascinates you the most?

Your answers to these questions should help you decide whose point-of-view you might wish to explore.

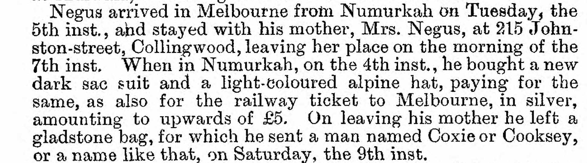

For example, anything I can find about my great-great uncle focuses on his crimes and sentencing, but there is a small detail in The Police Gazette about him visiting his mother while on the run. I am curious about what it was like for his mother, my great-great grandmother? What was it like watching her son being arrested and imprisoned? What support did she have, and did she attend the court hearings? This is the perspective that fascinates me most, especially as I know that she never learned to read and write.

Developing character

What do you already know from what you have already read?

Are you able to find out any additional information from other sources e.g. books, journal articles, newspaper articles or other archival material?

Consider your subject’s motivation. Why might they be behaving, speaking or taking action in the way they are? Even if you don’t know the answer, simply asking the question can assist you imagining, and perhaps understanding, what the experience was like for them. This may also help your reader to engage with your character and their story.

What would you have done in a similar situation? Would you have behaved in a similar or different way to your character?

Which Point-of-View?

Will you write in first person (write as if you are the character) or third person limited (uses he/she but your character is still the focus of the narrative; we only see what they see)?

Of course, these are not the only possible points-of-view, but they are probably the most relevant if your writing is focusing on a single person’s perspective.

Perhaps experiment with both points-of-view and see which one works for you. How does each version help you understand the perspective you’ve chosen to write from? What insight does it offer the reader?

Building the Story

Where will you begin your story?

Three potential narrative structures (although there are many others):

- chronological narrative (from beginning to end),

- a circular narrative (your story begins and ends at the same point)

- start at a dramatic moment within the story before going back to the beginning

What elements of conflict or tension are there? How might you develop these? Remember that conflict can be external between people, or between a person and the natural elements, or be inner turmoil, such as struggling to make a decision, feeling anxious or dealing with grief and loss. Conflict and moments of tension are often what makes a story engaging for a reader.

How does the story end? Is the conflict resolved in some way or will your story be open-ended, with no definitive conclusion? Will it end on a note of hope, a hint about the future (i.e. what happens after the conclusion of your narrative), or does it finish sadly?

Creating a Sense of Place

What do you already know about where the event/s take place?

Are there maps, images or documentary footage that can offer additional descriptive detail? While you may find books with visual material like this, there is also likely to be online resources that are relatively easy to find as well as via local museums and historical centres (sometimes also accessible online).

This audio-visual material might be of the people in the story (I recently found a mug shot of my bush ranger great-great uncle), but it can be particularly useful in helping you develop a sense of place in your writing. For example, I could search for images of Rutherglen during the 1890s, when some of John’s crimes took place.

Researching Other Additional Details

What information and clues can you find in the current book you are reading or studying?

Are there other books that offer additional information or alternative interpretations of the event/s you are researching?

Consider the event’s context. What else was happening historically, socially and politically at the time?

How was the event being reported in the newspaper? Did the journalist report factually, or did they add their own opinion or bias into the article? You may find articles about the event on Trove, a digital archive of Australian newspapers.

Are there differences between the way the events were reported at the time and the way researchers and writers view those events today?

Deciding on Genre and Form

Will you

- stick to the facts and write historical non-fiction?

- write a fictional account based on real events? E.g. The True Story of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey, which is promoted as a novel loosely based on historical events and people, but you let your imagination to fill in the gaps in your knowledge?

- experiment with creative non-fiction, where you use the narrative elements that might be considered novelistic rather than completely historical, although your work is well-researched. This form can come under criticism if inaccuracies or invented elements are identified, but it can certainly help your reader to immerse themselves in the story. E.g. Ned Kelly: The Story of Australia’s Most Notorious Legend by Peter Fitzsimons.

- play with narrative poetry or pen song lyrics?

- experiment with a hybrid text that combines two or more forms?

Where does the book you’re currently reading fit in to these possibilities?

Which style interests you as a writer? Why?

You may need to experiment before you decide which will work for the story you are telling and what suits your own writing style (or you may have a teacher who requires you to write in a particular genre).

Referencing

Did you find and use information from sources other than your imagination? Unless you chose the completely fictional route, this is highly likely. These might have been books, websites, newspaper articles, images, objects, maps or even directly from another person. It is important to give credit where it is due and acknowledge where we found any additional details. This will also help readers to see what is factual and what you may have creatively re-imagined.

There is no one right way to reference, but it is important to do so, and be consistent in the format you use.

Over to You

Which event and whose perspective will you focus on, and what decisions will you make about how to tell that story?

References

1. ‘Highway Robbery and Stealing from the Person’, Victoria Police Gazette, 28 December 1899, p. 415, Victoria, Australia, Police Gazettes, 1855, 1864-1924, Ancestry.com, accessed 27 July 2021.

2. Images taken from Victoria Police Gazettes, 1855, 1864-1924 via Ancestry.com.