Are there authors you believe you should read simply because they’re considered one of the literary greats, or have appeared on best seller lists?

For many years, Isabel Allende was that author for me.

My friend Cecilia had recommended I begin with Allende’s debut novel, The House of the Spirits. At the time, however, I wanted to know about the events of 11 September 1973, when Augusto Pinochet staged a military coup and begn ruling Chile with a bloody fist. Rather than dive into the magic realism of The House of the Spirits, I chose instead Paula, the moving memoir Allende wrote after the death of her daughter, but which included an account of her life in Chile and subsequent exile.

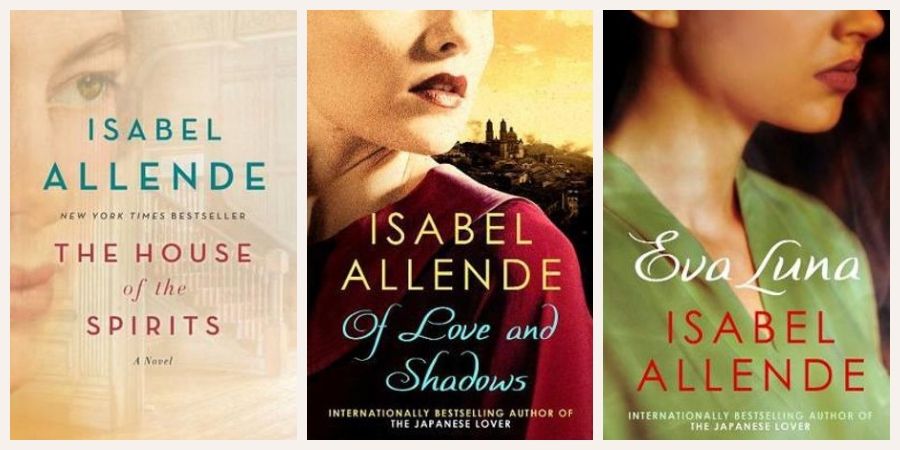

It was only when I visited Chile with Cecilia in 2015 that I finally read The House of the Spirits, and Allende’s second novel, Of Love and Shadows. Each explores to differing degrees the brutal impact of the Pinochet regime, and I realised that, at times, fiction has the capacity to reveal greater truths than non-fiction. Certainly, reading these two novels while visiting the country in which they’re set offered a whole new level of historical significance and impact. This was especially true as I also learned more about the experiences of both my friend Cecilia and the author Isabel Allende.

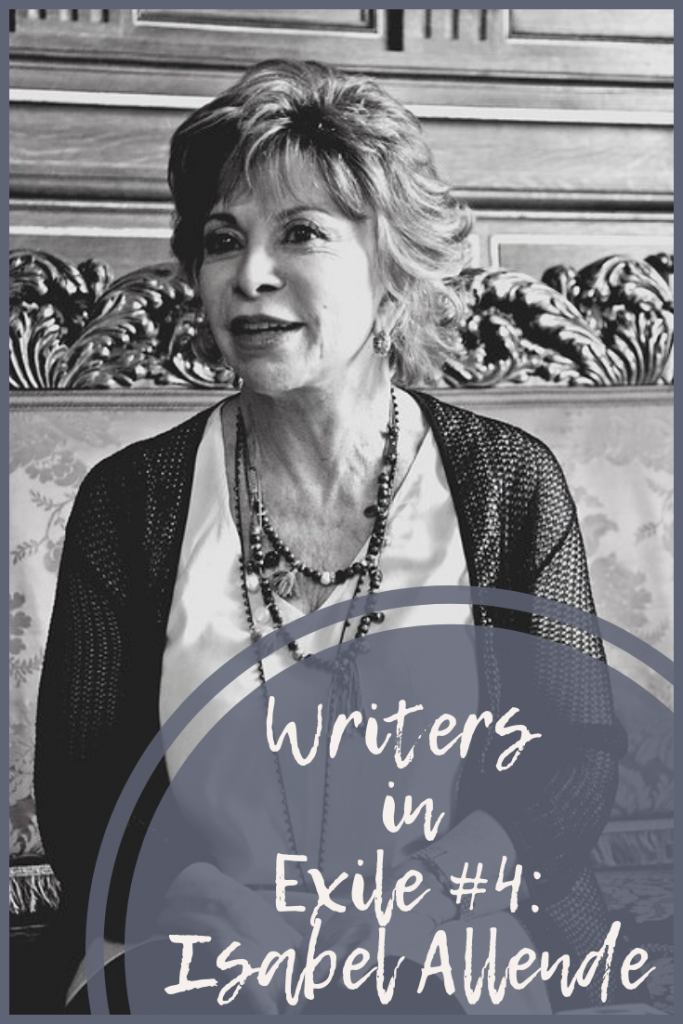

Isabel Allende: Journalist

Isabel Allende began her writing career as a jouarnlist, working in television and for magazines in Chile during the 1950s and 1960s. At the time of the military coup in 1973, the president was Salvador Allende, who also happened to be the first cousin of Isabel’s father.

‘Surely this will be the last opportunity I will have to address myself to you,’ President Allende told the people of Chile. ‘I will not resign … I will pay with my life for the loyalty of the People … These are my last words. I am sure that my sacrifice will not be in vain; I am sure that it will at least be a moral lesson which will punish felony, cowardice and treason.’

President Allende would be dead before the day was out.

Life Under Pinochet

In the early days of Pinochet’s rule, Isabel Allende became actively involved in aiding victims of the regime. In her memoir, Paula, Allende writes that she initially ‘had no sense of the danger.’ She dismissed the rumours ‘as exaggerations – until it was no longer possible to deny them.’

By mid-1975, friends warned her that her name was on blacklists, and she received two death threats by telephone. She found herself waking up sweating after hearing a car stop outside during curfew, and she broke out in hives. The final straw was when her children were cornered and threatened on the way home from school.

Isabel flew to Venezuela with a bag of dirt from her garden, whispering, ‘I’ll be back, I’ll be back.’ Five weeks later, when it was clear she could not return home, her husband and children joined her.

Exile

During those early days of exile, Isabel’s husband found work outside Caracas, where they were living, and her children begged her to take them back to Chile. Unable to find work in journalism, she took whatever she could find:

‘I learned very quickly that when you emigrate, you lose the crutches that have been your support; you must begin from zero, because the past is erased with a single stroke and no one cares where you’re from or what you did before.’

Isabel Allende and her family remained there in exile for 13 years, during which her children grew up, her marriage broke down, and she became a writer. Allende believes ‘there are moments in all human lives in which our fate is changed or twisted and forced to follow a different course.’ While she writes about the terror of living under Pinochet, and the ‘loneliness of exile’ she also acknowledges that if she’d never been forced to leave Chile it’s unlikely she would ever have become an author.

Becoming a Writer

On 8 January 1981, she began writing to her grandfather, who was dying back home in Chile. As a child, Isabel had lived with him in ‘an affluent house with no money’ after her father deserted the family. It was that house, and these letters to her grandfather, that formed the basis of her first novel, The House of the Spirits.

Each day, she would arrive home from a full day’s work, eat dinner with her family, shower, and then sit down at her portable typewriter:

‘… soon I lost track of where that strange letter was going, but I kept writing it for a whole year, at the end of which my grandfather had died and my first novel was sitting on the kitchen table.’

The House of the Spirits eventually found an agent, and publisher, in Spain. Allende began her second novel, Of Love and Shadows, on 8 January 1983, a date she considered lucky, and which now has become a tradition whenever she begins a new book. Of Love and Shadows was published in 1984, and a third, Eva Luna, in 1987.

It was only then that Allende dared to say, ‘I am a writer.’

Life in the US

Soon after the publication of Eva Luna, Allende visited the US for a book tour, where she met her second husband, Willie. As a result, she emigrated there to be with him. In 1990, after democracy returned to Chile, Isabel was faced with the choice of remaining in the US with her family, or returning to Chile and ‘starting from scratch’. She made her decision, becoming an American citizen in 1993.

In her second memoir, My Invented Country, she contrasts her experience as an exile with that of being an immigrant:

‘In the former instance, you are forced to leave, whether you’re escaping or expelled, and you feel like a victim who has lost half her life; in the latter it’s your decision, you are moving toward an adventure, master of your fate. The exile looks towards the past, licking his wounds, the immigrant looks towards the future, ready to take advantage of the opportunities within his reach.’

In 1996, she established the Isabel Allende Foundation, in honour of her daughter, with the proceeds of Paula. The foundation supports projects supporting women and girls. Allende continues to live and write in the San Francisco Bay area, ‘with one foot in California and the other Chile’.